THOMIA by Richard Simon. 2 Volumes, 81Chapters, 896 pages. Published by Lazari Press, Colombo (2025). Dedicated to the memory of his classmate, Richard de Zoysa.

James Chapman set sail for Ceylon from England in 1845, to become the first Anglican Bishop of Colombo. He was studying Sinhala on board the Malabar. Chapman was determined to embark on the greatest mission of his life, to create S.Thomas’ College, to resemble his alma mater Eton and his King’s College Cambridge.

Simon’s epic rendering spans two hundred years of British colonial Ceylon and post-independent Sri Lanka’s political history, told as “The entangled histories of Lanka and her greatest public school”.

This work creates a living atmosphere for events that influenced the greater British colonial process in Ceylon. In the author’s bid to intertwine the complex relationship of church and state of those times, he unravels fascinating socio-political insights of elite formation in Ceylon.

In 1851, opposite the Port of Colombo in Mutwal, forty-five boys drawn exclusively from the upper ranks of Ceylonese society sat for lessons in a Cadjan hut under a massive Banyan tree, and S.Thomas’ was founded.

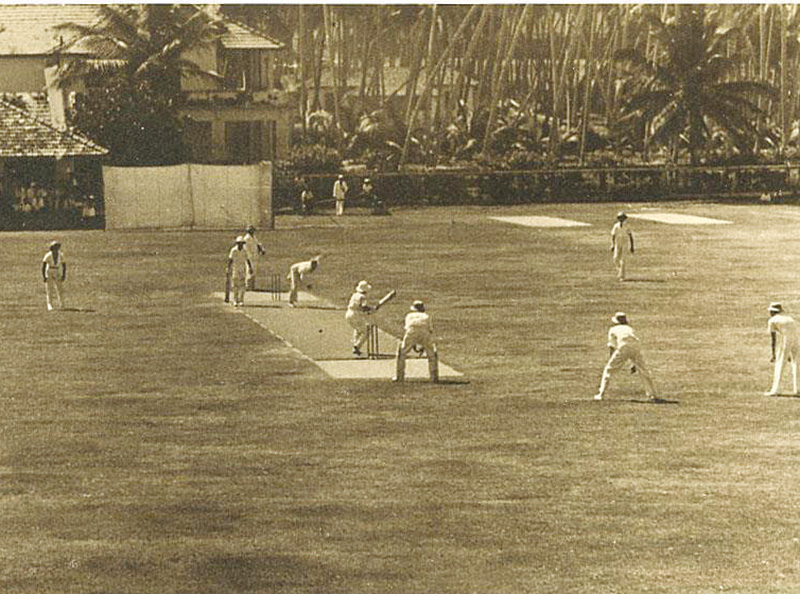

They were taught Latin and Greek and English, fed on Etonian roast beef and plum pudding, and learnt to play cricket. Ceylonese who could afford it, were only too eager to educate their sons, after the manner of the British upper classes.

The motto of the school was the same as Eton, Esto Perpetua, be thou forever.

Despite the belief that the divinely ordained purpose of the empire was to bring Christian salvation to the ‘heathen’, just three years before the school was founded, in 1848 the Kandyan Sinhalese in the highlands had rebelled. They were asking the colonial government to uphold the Kandyan Convention to protect Buddhism.

Kandy was the last Sri Lankan kingdom to fall to the British in 1815, when the Kandyan Sinhala aristocracy betrayed the country’s last king, a minority Tamil to the British, and signed the Kandyan convention. The island became Ceylon, with English as its official language.

After the colonial government resumed custody of the sacred tooth relic of the Buddha, and supposedly supported the protection of Buddhism under the Kandyan Convention, English Christian clergy protested the “re-connection of the British government with Buddhist idolatry”. Bishop Chapman distanced himself from his clergy on the issue, as his Anglican priests rebelled against him.

This voluminous work departs from the standard well-researched history, or the accepted norms of political analysis. It ventures into the creative realm of writing. Simon stamps his mark without any inhibitions, to tell his story. This makes this monumental work a pleasure to read.

Fifty years later in 1901, a Christian boy from a Buddhist family named Don David Hewavitarana walked out of S.Thomas’. He had not been allowed to be absent, on the holiest Buddhist Vesak Day. He was destined to lead the nineteenth century Buddhist revival in the island as Anagarika Dharmapala, and become the ideologue of ethno-religious Sinhala nationalism.

However, in schools like S.Thomas’ founded by Christian missionaries, it was a boy’s individual character and abilities, rather than his blood or his inherited advantages that mattered. It was in these schools, the concept of Ceylon as a diverse but integrated modern society first took hold.

Born and nurtured in the high summer of imperialism and English educated, these boys were to become the men who cast long shadows over the landscape of Sri Lankan history, as the sun declined in the West.

The sensitive subjects of discussion in this writing have made demands on the writer to carefully balance the contents of the events he describes and documents. It is neither an anti-imperial work, or a pro-nationalist treatise. Simon achieves objectivity of reportage; by his selection of men and matters, in the massive canvass he has dared to unfold.

Thomia as a testimony of those times has to be viewed in context of Victorin rule at the helm of the empire. The attitude of the English was clear when British historian and politician, Thomas Macauly famously said, we will create in our colonies those who are like us in attitude and language, only different in the colour of their skin.

At the outbreak of World War 1, many old boys of the school were fighting in the frontlines in Europe and the Mediterranean. Many Old Thomian tea planters fell into action. One of them, Second-Lieutenant Basil Horsfall was the first Ceylonese to be posthumously awarded Britain’s highest military decoration, the Victoria Cross for bravery.

Before the war ended, the 1915 Sinhala-Muslim riots led to events that marked the beginning of the end of British rule in the island. It began with a Muslim mob obstructing a Buddhist religious procession on Vesak Day, going past a mosque in the Kandy district.

An Old Thomian, Captain of the Guard Henry Pedris, a Buddhist, was accused of incitement to riot and using firearms. He was sentenced to death. Warden Stone interceded for Pedris’s life. An appeal was made to the King but was of no avail. Pedris was shot dead by a military firing squad.

Among Old Thomian Sinhala Buddhist leaders imprisoned was Don Stephen (D.S) Senanayake. He was shown the chair, still dripping in blood, to which Pedris had been tied and executed, and warned of the fate that awaited traitors to the crown.

The execution of Pedris is often cited as the moment the cry for independence was born. The English Governor was recalled to England. Senanayake was destined to lead the country to independence.

The Anglicised elite of Ceylon, who identified themselves with their overlords, considered itself an honour to volunteer their lives on behalf of ‘King and country’. One of the last to go to the front during the Second World War was a future first Ceylonese Warden of the School, Canon De Saram. When he reached Port Said the war ended, and he saw no action.

However, in 1941 it was a Thomian who led a mutiny against the British in an outpost of the empire, in Cocos Islands between Ceylon and Australia. Influenced by Japanese English language propaganda broadcasts, Bombardier Gratien Fernando began to believe in Asia for the Asiatics and was in sympathy with Japanese war aims.

He led a failed mutiny which led to his execution, along with two other Ceylonese, Gauder and De Silva. They refused any offer of clemency. It was the only execution for mutiny during the Second World War by the British. Fernando’s last words were “loyalty to a country under the heel of the white man is disloyalty”.

At S.Thomas’, Senanayake had been a formidable wrestler. He played for three Royal-Thomian cricket matches, and had an enormous talent for natural authority and the ability to make himself loved. Stone wrote for the departing Senanayake that his conduct was irreproachable, and his influence most salutary.

In the outside world Senanayake the affluent planter was noticed as being indifferent to the divisions of race, caste and faith that meant so much to many other educated Ceylonese.

S.Thomas’ itself was facing its sunset at Mutwal. The coal dust from the expanding port had sounded its death knell. Warden Stone was entrusted with the task of taking the school to a fishing village seven miles away from Colombo. It was to Mount Lavinia.

Stone first looked at the abandoned stately, country residence of a former governor overlooking the Mount Lavinia Bay. The church had no money to buy the mansion, which was to become the famous Mount Lavinia Hotel.

After sixty-seven years, in 1918 the exodus to a half-built school was to see another generation of Thomian schoolboys sitting for lessons in Cadjan huts again. It was a new beginning, for boys who were accustomed to all the comforts of wealth and privilege.

But for Stone there was no grumbling or murmuring. He was an Englishman of working-class origins who had been to Cambridge, and had known a hard life. Stone held the reins of the school for a quarter century, from Mutwal (1901) to Mount Lavinia (1924).

He was determined to build the real Eton of Ceylon in Mount Lavinia, and nurture a generation with the best that Christian missionary education had to offer, to a country heading for independence.

It was to become a labour of love, for which every old boy was asked to contribute. The new school was begun to be built with money raised by selling the Mutwal school to the government for the Port. It was not enough for the grand edifice of Corinthian and Byzantine architecture, with a quadrangle and a cricket ground.

It would resemble one of the colleges of Oxford or Cambridge. It would overlook the blue waters of the Indian Ocean, in a garden of coconut palms swaying in the sea breeze, and become the iconic “School by the Sea”. (To be continued)

Reviewed by

by Shavindra Fernando

from The Island https://ift.tt/5DyhP2I

No comments:

Post a Comment