Six Charges, 700% More Expensive:

Imagine walking into two shops selling the same product. In the first shop, you pay a simple 0.6% fee. In the second shop, you’re hit with a bewildering array of charges from multiple entities, and by the time you’re done, you’ve paid 2.27%. And that’s for a complete transaction: buying and selling.

The Shocking Numbers

Sri Lanka loves to say it wants to “develop the capital market.” But the way we charge investors tells the real story – a story of policy confusion, fee-layering, and a system designed to favor big players while suffocating small retail investors.

The evidence isn’t hidden. It’s printed clearly in every contract note that brokers issue.

Think about what this means in real terms. If you’re a teacher, government servant, or small business owner investing Rs. 100,000 in shares, you’ll pay approximately Rs. 2,270 just to complete a buy-sell cycle in Sri Lanka. In New Zealand, that same transaction costs just Rs. 300.

Sri Lanka is nearly four times more expensive than New Zealand – for the exact same act of investing.

Death by a Thousand Cuts

* Brokerage (negotiable, but only if you’re wealthy)

SEC Fee (Security Exchange Commission)

* CSE Fee (Colombo Stock Exchange)

CDS Fee (Central Depository Systems fees)

* STL (Share Transaction Levy)

Clearing Fee

* Foreign Brokerage for foreign transactions

* Various “special fees” are added periodically

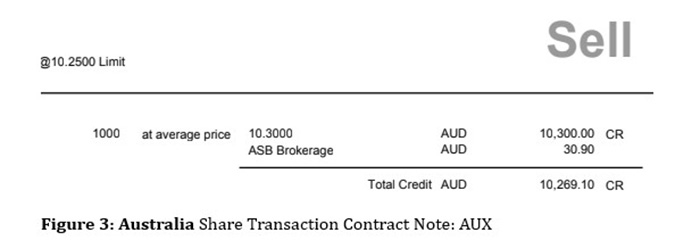

Sri Lanka’s stock trading contract note reads like a mini-budget speech (Figure 1). Meanwhile, most modern markets charge one number. For an ordinary person trying to understand their contract note, it’s nearly impossible to figure out what they’re actually paying and why. Figures 2 and 3 show the stock trading “Sell” contract notes for a New Zealand Stock Exchange transaction and an Australian Stock Exchange transaction, (“Buy” contracts are similar) respectively.

The Rich Get Richer – By Design

Here’s where it gets truly disturbing. While small investors are locked into these punishing charges, the CSE allows brokers to negotiate lower fees for large transactions – typically those exceeding Rs. 100 million.

Let that sink in: If you’re a retail investor putting in your life savings of Rs. 500,000, you pay the full 2.27%. But if you’re moving Rs. 100 million, you get a discount.

This isn’t just unfair – it’s a systematic transfer of wealth from small investors to large players. The very people who need protection are subsidising the fees for those who need it least.

In modern markets like India, New Zealand, Canada, and Japan, all investors pay the same percentage. No negotiation. No special deals behind closed doors.

The Market Manipulation Connection

This two-tier system has darker implications. Large players, already enjoying preferential fee structures, have repeatedly been caught manipulating the market. The Securities and Exchange Commission has filed numerous cases against major investors for price manipulation, insider trading, and other violations.

These large players can:

* Move in and out of stocks quickly due to lower transaction costs

* Manipulate prices knowing small investors can’t react fast enough (their costs are too high)

* Accumulate positions while retail investors are trapped by the fear of paying 2.27% round-trip costs

Sri Lanka’s fee structure encourages large speculative swings, discourages genuine retail participation, creates an uneven playing field, and opens doors for manipulation and cornering of illiquid stocks.

The Ethical Bankruptcy of Regulatory Charges

Let’s call this what it is: regulatory authorities charging fees that actively harm the market they’re supposed to develop are ethically bankrupt. In most countries, regulators protect investors. In Sri Lanka, they bill investors. Every trade finance the regulator (SEC), the exchange operator (CSE), the clearing house (CDS), the broker, and the government (through VAT).

This is ethically questionable because:

Regulators must be neutral – not profit from transactions

Charging retail investors to fund regulation creates a conflict of interest

It reduces trust, especially after repeated market manipulation cases

When regulators impose charges that make it unprofitable for ordinary people to invest, they’re not protecting investors – they’re protecting their own revenue streams at the expense of market development. When exchanges allow discriminatory fee structures, they’re not creating a level playing field – they’re creating a rigged game.

Why Sri Lanka’s Market Cannot Grow

Sri Lanka keeps asking: “Why is liquidity so low? Why don’t more people invest? Why doesn’t the stock market support economic growth?” Based on my research, using AI tools, here’s a comprehensive comparison table of stock market participation across the countries we mentioned:

Sri Lanka stands out negatively. The CSE has 284 listed companies representing 20 business sectors. Despite having a population similar to Australia (22 million vs 26 million), Sri Lanka has an estimated 50-100 times fewer stock market participants.

According to the Central Depository Systems (CDS) Annual Report 2024 for the Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE), the total number of local account holders (traders/CDS holders) was approximately 706,864 in 2024, up from 693,415 in 2023. The number of foreign account holders was 11,082 in 2024 compared to 10,937 in 2023. This places the total number of traders around 718,000+ in 2023-2024.

Critical Implications

Sri Lanka’s stock market participation rate, estimated at a low 3-4%, starkly trails regional peers such as India, where participation hits 6-8%, roughly two to three times higher. This gap highlights a critical structural problem in the Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) ecosystem, where high fees averaging 2.27% combined with low participation create a vicious cycle that severely impedes market development. The core issues are both systemic and strategic.

The Marketing Failure: A Stock Exchange That Doesn’t Want Customers

Unlike its counterparts globally, the CSE remains more akin to an exclusive club rather than an accessible retail investment platform.

Where India’s National Stock Exchange (NSE) partnered with fintech innovators to create user-friendly investment apps while the CSE’s outreach is limited to sporadic seminars mostly attended by brokers and affluent investors. The CSE doesn’t want millions of small investors; it wants thousands of large ones who won’t complain about the fees.

There are no robust nationwide campaigns demystifying investing, no telecom partnerships to penetrate rural markets, and the mobile apps are not intuitive and fail to simplify account opening processes as expected. The CSE’s web and social media presence remain outdated, and when India onboarded over 40 million retail investors in three years via aggressive digital marketing, Sri Lanka struggled to add even 40,000 investors. This is not accidental, but symptomatic of an institution that profits more from high fees on lower volumes than from a broad base of smaller investors. The system favors wealth extraction from a few large players while discouraging retail participation.

Bureaucratic Ossification: When Vision Dies in Committee Rooms

The disconnect between high market returns (close to 50% in 2024) and low investor participation underscores the urgent need for the CSE to radically change course from a fee-heavy, opaque, bureaucratic institution to a transparent, technology-enabled, investor-friendly market. Unless Sri Lanka’s capital market astrology embraces inclusive, technology-driven, and simplified structures combined with aggressive marketing and retail investor protection, it will continue to underperform relative to regional peers, hampering broader economic growth and wealth creation.

Marketing Malaise: How the CSE Misses the Retail Wave

There are no nationwide campaigns to demystify investing. No partnerships with firms like financial institutions and tertiary education establishments, such as universities, where eligible customers are abundant and to reach rural areas. When India added over 40 million new retail investors in just three years through aggressive digital outreach, Sri Lanka couldn’t add 40,000. This isn’t accidental – it’s the natural result of an institution that makes more money from high fees on low volumes than it would from low fees on high volumes.

Bureaucratic Ossification: When Vision Dies in Committee Rooms

The CSE’s administration suffers from a fatal combination: colonial-era bureaucratic mentality married to a complete absence of strategic vision. While global exchanges have transformed into technology-driven, investor-first platforms, the CSE remains trapped in a time warp protecting its turf and revenue streams. Decision-making moves at the speed of a government file, while markets move at the speed of light.

The result is an exchange governed by administrators rather than visionaries. When Singapore launched a comprehensive digital trading ecosystem, when India implemented T+1 settlement cycles, when New Zealand simplified its entire fee structure to one transparent charge, Sri Lanka’s was busy protecting the status quo. There’s no long-term strategic plan to achieve even 10% retail participation. No vision for how Sri Lanka’s capital market fits into the economy of 2030. The CSE operates like a government department completing its KPIs rather than a dynamic institution building national wealth. The entire ecosystem – from the SEC to CDS to brokers – protects a broken system because they all profit from it.

Whenever the question of low retail participation comes up, officials trot out the same tired excuses: lack of investor awareness,’ ‘risk appetite,’ budgetary constraints for promotions.’ What they never admit is the elephant in the room, Sri Lanka’s fee structure. Charging 2.27% in a fragmented, opaque system while allowing negotiated rates for the wealthy isn’t market design, it’s a wealth extraction scheme dressed in regulatory language (Figure 3).

Add to that a lethargic marketing approach for attracting a wider population. Instead of proactive campaigns, digital engagement, and investor education, the system relies on outdated methods that fail to inspire confidence. The result? A market that moves backward while global peers surge ahead.

Our regulatory authorities have created a system that achieves the exact opposite of what a stock market should do. Instead of encouraging saving and investment, we punish it. Instead of attracting retail participation, we drive small investors away. Instead of ensuring fairness, we let the rich negotiate better terms.

The Bottom Line

The Colombo Stock Exchange and its regulatory framework aren’t just failing small investors – they’re actively working against them. No stock market can flourish when fees punish participation and policy rewards big players while suffocating small ones.

If Sri Lanka wants a real capital market – not just a slogan – it must not only stop taxing retail investors to fund inefficiencies and start building a market that ordinary citizens can finally trust, but also, they should actively promote the retail participation with more promotional activities to reach them by making collaborations with relevant firms such as financial institutions and tertiary educational establishments, especially universities.

Until someone in authority has the courage to blow up this exploitative system and start fresh, ordinary Sri Lankans will continue to be better off keeping their money under the mattress.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

from The Island https://ift.tt/XsPOfv4

No comments:

Post a Comment